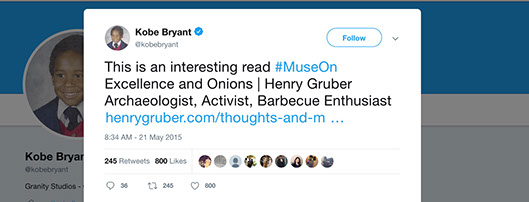

This was the site of my blog, at one point, but I have briefly taken it down. I reproduce, for the historical record, three of my most "famous" blog posts: my reasons for supporting Bernie in 2016;the use of history; and one on excellence, onions, and Kobe Bryant.

On Excellence and Onions (April 18, 2014):

I received pushback on aspects of my last post, most of it thoughtful and much of it, unfortunately, through private channels; many concerns were overlapping and could have sparked quite the debate. Most addressed the intersection between the ‘death of God’ (which need not be about divinity) and the development of a culture obsessed with the gratification of the body through consumption. Good points were raised; mistakes on my part were admitted; further thoughts on the subject will be refined and reorganized. But not today.

Today I'll write about the intersection between onions, Seneca, and Kobe Bryant.

I’ve recently realized that onions are my favorite vegetable. Caramelized onions have always been a special treat. For my birthday, I made myself 20 pounds of pickled onions, and made another (albeit smaller) batch last weekend. When we roast pigs at my house, we put a bed of onions underneath the meat to soak up the drippings. I like onions raw in salads, fried on tacos, and disintegrated in curries. They are versatile, delicious, and the basis for almost every one of my favorite dishes.

Onions, though, are neither memorable nor generally considered ‘excellent.’ To say that they are my favorite vegetable privileges them over vegetables like carrots or asparagus or peppers or (the overrated) kale. Each of these vegetables is only more excellent than onions, however, when viewed for a specific purpose (whether that be a salad or a sauce). None of them can match the the onion’s breadth. When I personify onions, they have more fun. When the chili pepper wants to go hang out with the Indians or the Mexicans, the onion can go when the asparagus can’t. “Hey onion!” the kale might cry, “wanna come to a salad party?” The onion can always say yes.

So why focus so much on onions, on a vegetable so unfocused that until recently onions had never even entered my mental tournament of ‘greatest vegetable’? Because the problem of the onion—focus and breadth and excellence—is currently one of the major problems in my life.

I regularly pursue hobbies to the barest level of mediocrity and then abandon them. I start projects that die around the halfway-done mark. I am a chronic dabbler.

I began to really be bugged by this breadth this past quarter, because I feel that I have found a field—ancient history, archaeology, classics—that I can see myself pursuing for the rest of my life. It’s a tough field, however, with lots of names and dates and declensions and participles and meters and all sorts of types of ceramics that need to be memorized. But, to briefly table my humility, I think I could be great at it—I just need to dedicate myself and put in the time to master it all.

That challenge, to dedicate myself to my newfound passion (at the exclusion of everything else, seems to be the subtext), was posed to me by a text I read last quarter: “On the Shortness of Life,” by the Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca. The short essay, which is quite excellent, addresses the problem of wasted time: “We do not have a small amount of time,” he writes (in my loose translation), “but we waste it greatly. Life is long enough as it is given to complete even the greatest things, if it is all used well.”*

For Seneca, that means stepping outside the rat race of Roman politics and pursuing a life of studied leisure, putting aside the honors and flatteries and money-making schemes of the Roman elite in favor of the life of the philosopher. Seneca’s hypocrisy aside, it is a picture of a certain ancient ideal. For those of us in the modern world, who may not have the means or desire to retire to our country estates to practice dying every day, it is a clarion call to make the most of what we have, to make the most of that one utterly finite resource placed at our disposal: time.

Kobe Bryant makes the most of his time. His workout routine is legendary. His discipline (when it comes to basketball, at least) is exemplary. He tries to make 800 shots before anyone else shows up to practice. As a recent profile in the New Yorker suggests, his life is above all dedicated to becoming the best human to play the sport of basketball in the history of the world. Kobe Bryant is not a dabbler.

Whenever I think of Kobe, he is a challenge to my dedication. If I wanted to be as good an ancient historian as Kobe is a basketball player, I would be in the gym every morning at 4am making sure I parsed 800 verbs before anyone else shows up for class.

I spend more of my life studying the ancient world than I spend on anything else. But I don’t do it at Kobe levels. I put in a full week of work, and I’ll try to do something else on the weekend. I like learning Greek, but I also like practicing yoga. I love reading Ammianus, but I also love reading Michael Pollan and Andrew Sullivan. I like cooking and watching baseball with my friends. And don’t even get me started on Republican intrigue, whether it involves the Gracchi or the Palins. I don’t know if I want to be the greatest ancient historian ever badly enough to sacrifice all those things.

Even within the (narrow) field of late antiquity, I can’t decide whether to focus on the persistence of Roman fiscal structures or the archaeology of urban change or overlaps in the material culture of churches and synagogues or even something totally different like religious reinterpretations of ancient philosophical praxes. None of that even mentions the recent professorial suggestion that I should switch to being an (early) medievalist rather than a late antiquarian. But you don’t get a PhD and a tenure track job in breadth.

For Seneca, the goal of the life of rigorous philosophical relaxation was the happy life, the vita beata. When Diotima asks Socrates what happens to the person who reaches the goal of human existence, who sees the Form of Beauty, he replies εὐδαίμων: he will be happy.* We live in a world today where we can broaden our definition of happiness beyond the ideals of a landed Mediterranean elite, but still: we should want to be happy. After all, if we are miserable, what else matters?

Can you be happy and ignore every aspect of your life except one? Does any amount of success in a given field—even a field that you love more than anything else in the world—justify sacrificing all the things that make life worth living? Given the inevitability of our utter disintegration, the pure pleasure of just living in the world, and the nothingness of an eternity that will make even our proudest accomplishments into nothing more than two vast and trunkless legs of stone standing in the desert, do we not owe it to ourselves to seek out eudaimonia?

In a 1999 interview, a 20 year old Kobe Bryant was asked whether he was happy. “I guess, maybe. Not really,” came the response. “I really don’t believe in happiness.”

That was Kobe Bryant just a couple years removed from taking Brandy to prom. He may be the greatest of all time (he probably isn’t), but I don’t know if I can abandon all hope of good living for professional greatness. I don’t know whether I could sacrifice my one shot at life on the altar of history, even if it meant that at the end of the day a student a century from now felt obligated to skim my book for a seminar.

Maybe I would rather be an onion than an asparagus. Onions have layers.

*De Brevitate Vitae, 1.3: non exiguum temporis habemus, sed multum perdidimus. satis longa vita et in maximarum rerum consummationem: large data est, si tota bene conlocaretur.

** Symposium, 304e7. If you are going to complain that happiness doesn’t properly translate eudaimonia, well, I am sorry. It’s a toughie. Suggestions are welcome.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Why Study History? (May 25, 2014)

In the first book of The Peloponnesian War, Thucydides, the first real historian in the western tradition, defended his use of facts, his lack of embellishment, and his creation of a new genre of writing based on painstaking research: “Perhaps it will be joyless,” he says, “to hear this history recited, because there is nothing legendary inserted in it. But someone who desires to look into the truth of things done and, as is the condition of humanity, which may be done again, or at least things like them, will find this to be abundantly serviceable. It is compiled more as an everlasting possession than something to be recited once in a competition.”*

Thucydides is not the only historian to open his works with a justification of his craft. History is a self conscious discipline, written by those who step back from the oars of their society and try to see the whole river, its tributaries and its eddies, not from anywhere on the boat but from above it. There is something a little self indulgent, though, in giving up the oars, and anyone claiming that’s because of the relative labor involved has never spent time in an archive. Rather, there’s a sense of abdicating responsibility for the future by submerging oneself in the past.

So here I am, justifying to myself as much as to others why I—someone who has dabbled in politics and pulled back, thought about business but shrunk away, who feels compelled to fight for justice and a better world but just can’t quite commit—have decided to become a historian.

The easiest answer is that I like history; one of my first memories is of driving with my family through the Italian countryside, my father behind the wheel regaling me with stories of American heroism in the Second World War. We talked about Midway, and then the Italian campaign, and finally the thought that maybe at that moment fifty years before some GIs had been catching a little sleep in the village through which we were driving.

But enjoyment is not a sufficient reason to pursue a discipline. There must be some higher redeeming factor making it a worthwhile way to spend a life. This thought has driven me to interrogate my discipline, to think through the benefits of a study of history, and to justify why I—who could be dedicating my resources and privilege to fighting climate change or unjust labor practices—have instead, like Thucydides, taken up the pen to recover the past.

Thucydides wrote that the reason to study history was because of the cyclical nature of human society; things happen, and happen again, and to understand the past is to be prepared for when similar situations will inevitable arise. ‘Those who don’t know history,’ as the old adage goes…

I disagree with the notion that history is supposed to show us the unchanging nature of humanity and merely serve as a guiding principle for future action. That is view limits what history does and can do, and it limits the important parts of history to those fields (like politics, diplomacy, and military history) where we might see patterns and learn from prior mistakes. There is a place for that—one of my favorite history books, Archer Jones’ The Art of War in the Western World, is filled with sentences that compare the efficacy of flanking maneuvers by Alexander’s companion cavalry to those by Patton’s tanks or analyze the comparative force:space ratios in Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia and Henry V’s failed Agincourt campaign. But that is not what the contemporary study of history should be about.

History today should be less about cycles than about change, less about modes of combat than modes of thought.** One of the main projects of global capitalism is to eradicate from our minds the idea that any other type of society could exist. It is not enough to proclaim the triumph of capitalism over other systems; that there are other possible systems is dangerous and must be denied. This is done both intentionally and accidentally, and it goes back to Adam Smith, who could not comprehend a human nature free from an inborn propensity to truck, barter, and trade. Today, the arguments are more insidious and less erudite, and they attack us from billboards that commoditize every space in our world and apps that commoditize every aspect of our time.

This is not helped by the overall ignorance of the most people, Americans certainly not excepted. We have, as a people, an incredibly limited historical consciousness. This is inexcusable. The human race has reached a point in its self-awareness where it has ample evidence of 1) the fact that the organization of makeup of human societies can radically differ across time periods and places and 2) the actual specific ways in which those societies differ from each other. I would posit that this is a combination that no other time period has seen, and it gives us an opportunity and a responsibility. Part of the radical freedom inherent in a post-Enlightenment world is to realize that as a society and a species we determine our own meaning. This is part and parcel with the radical freedom that makes it so hard to us to find purpose as individuals, but where it can lead to individual helplessness it can lead to societal innovation.

The great insight of Marx was not anything about the nature of Capitalism or the labor theory of value; both of those, in fact, he probably got wrong. But his great insight was that humans are uniquely positioned to change our relationships with each other, with production, and with the world. We choose our own form of life. But we can only do that with a full historical consciousness of what other options are out there and what other options have been tried.

Without an understanding of how people in the past lived, we cannot understand the fully non-determinist nature of human nature. If we ignore history and fail to recognize that the way we live now is not the way we have to live, we not only give up all hope of changing the world but we give up the ability to even recognize that the world can be changed.

So to return to Thucydides, I am not studying history because I want to teach the future citizens of our Republic how to deal with a rebellious colony on the Athenian model, or how to poorly manage your empire, or how (not) to attack Sicily. While those are all valid lessons we can take from histories, the lesson of History is far more basic, but far more profound: it is that the world changes, and we can change it, and the way that we look at the world now will not be the way that people in the future look at it.

We must become historically conscious so that we can transcend our present. And as a historian, it will be my job to rouse that historical spirit and that, I think, is a goal worth pursuing.

*Thucydides, Peloponnesian War, 1.22.4. “καὶ ἐς μὲν ἀκρόασιν ἴσως τὸ μὴμυθῶδες αὐτῶν ἀτερπέστερον φανεῖται: ὅσοι δὲ βουλήσονται τῶν τε γενομένωντὸ σαφὲς σκοπεῖν καὶ τῶν μελλόντων ποτὲ αὖθις κατὰ τὸ ἀνθρώπινον τοιούτωνκαὶ παραπλησίων ἔσεσθαι, ὠφέλιμα κρίνειν αὐτὰ ἀρκούντως ἕξει. κτῆμά τε ἐς αἰεὶμᾶλλον ἢ ἀγώνισμα ἐς τὸ παραχρῆμα ἀκούειν ξύγκειται.”

**I bet you thought I was going to say modes of production.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Feelin' the Bern (October 1, 2015)

I have decided to vote for Bernie Sanders in the 2016 Democratic Primary. This was not an easy decision; I like Hillary. I find her more than likeable enough. So much of my family—both of the biological and chosen variety—is supporting Hillary, however, that I feel obligated to give some explanation of why I am feeling the Bern. This essay will have three sections. The first is a summary of my current political beliefs, more or less a meditation on the Obama years. The second is my positive case for Bernie, and the third is a response to possible counterarguments. It is not designed to persuade but, if you share my political views, you may be persuaded. Read at your own peril!

I volunteered for Barack Obama in 2008. I worked on his reelection campaign. I count his two election night’s among the best nights of my life. I think he’s done a heckuva job. Healthcare was huge. Saving the economy was big. Knowing how to be a leader on marriage was smart—especially realizing that sometimes being a leader means not leading, but broadcasting that you’ll allow yourself to be pulled. Think about the DREAM Act. I think he’s done good stuff on banks, that his foreign policy has been better than average, that the Iran deal has the potential to be world historical.

He’s not perfect—he royally fucked up the surveillance state stuff, and I think that in retrospect inaction on climate change may mar his legacy. But for the most part, and in the face of bitter, nativist, racist opposition that has at times put the personal destruction of a fundamentally decent man not just above the good of the country but against all of its traditions of governance, Obama has done well. Fifty years from now he will be considered one of our greatest presidents.

But while Barack Obama has done a lot of good things for the nation, the nation itself is not well. It faces threats from three types of enemies. The first are foreign. The second are domestic. And the third are structural.

Foreign enemies have often threatened the United States, and today is no different. We, and the rest of the civilized world, face a fundamentally barbaric threat in ISIS. It is my personal belief that sooner rather than later the world will fall into a clash of civilizations, not the one drawn on facile religious lines by Huntington et al. but one based on the interreligious lines of fundamentalist intolerance against the liberal post-Westphalian tradition, and in that fight as many Evangelical Christians and Orthodox Jews as ISIS members will be massed in the host arrayed against us. But, between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton, I don’t see too much difference on foreign policy. They are both technocrats who lean away from war—Hillary less so than Bernie—and will defer to the security apparatus and the military industrial complex.

As for domestic threats, those come from the Republican Party, which over the last eight years has responded to its absolute failure of governance during the younger Bush’s administration by shedding any pretense of legitimate political aims and abdicating all responsibility toward the nation. I will not here repeat the litany of obstructions, parliamentary tricks, idiotic policy proposals and suicidal political strategies that the GOP has repeatedly put forward over the last few years. I will just note that John Boehner just quit. The Republican candidates live in a fantasy world, and God help us all if any of them should become President.

So a Democrat must win. Really, any of our candidates would be better than any of theirs, and so by compromising our ability to win we would not only disservice the Democratic party but abdicate our duty as citizens. Why, then, vote for Bernie? Why not vote for Hillary, who must—must!—have a better chance than Bernie to win a national election. He is, after all, a 74-year-old Jewish socialist from Vermont. If voting for him were to make a Republican more likely to win, voting for him would be a dereliction of duty.

But here’s the thing: in a world where Hillary Clinton loses the nomination to Bernie Sanders, things have gone so wrong with her campaign that she would get smoked by Marco Rubio. Hillary Clinton is an awful campaigner. She was bad in 2008; she’s been bad so far in 2016. This isn’t to say she’s a bad politician—there’s a lot more to politics than slapping backs and kissing babies, and she’s good at raising money and building alliances. Everything suggests she’d be great at the actual process of governing. Her head is in the right place, her policies are good, and she would probably get a lot done. But she is bad at campaigning, and if the slow trickle of scandals and the dull drone of flagging enthusiasm mean that she loses to Bernie, well, she wasn’t going to win the general anyway.

But that’s not the reason I’m voting for Bernie. That’s just how I can sleep at night knowing I’m not helping Ted Cruz. The reason I’m voting for Bernie Sanders is because of the third threat. The third threat is a structural enemy. We live in the age of Piketty. We are witnessing the growth of an international capitalist class whose power comes not from promoting policies that help people but from wielding huge sums of money to subvert democracy. I won’t go into the statistics: just watch a Bernie Sanders speech. The world is becoming less equal. While spiraling inequality might not be bad in and of itself (I think it’s fine, as long as everyone is doing better, but they’re not), it points to a greater problem we face: the fates of the elite are, in the short run, becoming less and less tied to the fate of the rest of the nation.

This again, isn’t bad in itself—nationalism is pretty awful—but I happen to really like America. And if you look back, the untethering of the fate of elites from the fate of a state precedes the end of that state, and it’s never pretty, for the elites or the rest of us. The problem we will face in the future is a disjunction between the fate of the United States and the fortunes of the powerful within her. Like Rome in the waning days of the Republic (speaking of facile analyses) we have a system that is losing the trust of those in it. And we need to make a statement.

I am voting for Bernie Sanders not because I think that anything that he will do in office will be meaningfully different from what Hillary would do. Government will still be divided—gerrymandering has seen to that. State governments will be in the hands of Republicans and the next President will, whatever his or her views (and I still think we should assume it’s a her), have to compromise. In fact, given her ability to be flexible, I think Hillary could get a more done than Bernie. She would probably be a better President. But the next president has only one main job: to keep everything that Obama has done (but mainly healthcare) in place until it becomes permanent, in the face of Republican opposition that refuses to see reason and facts. Both Hillary and Bernie are going to do this and do a good job at it. Anything else is icing on the cake or, hopefully, the arctic.

What a Bernie Sanders Presidency would be is a symbolic victory against the forces of crony capitalism and the dominance of American life by a so-called meritocracy that adopts progressive positions out of a sense of charity towards the less fortunate and a paternalistic discomfort with its own privilege that, in a different age, we might call noblesse oblige. The world that we live in is a hyper-liberal (in the bad sense of the term) world in which money has devalued all other values and the market has become enshrined as a new god. That is awful. We need to resist that.

But we need to resist it in a smart way. Those of my radical friends out there are reading this and thinking that I have developed a false consciousness, that I have bought hook line and sinker the illusion of free choice while remaining constricted within the two party system of the US. I accept those criticisms, and say, ‘so what?’ Politics is the art of the possible. Over the last eight years the slow and steady politicking of my second favorite President has brought more good to the American people than the posturing of radicals has in decades. We need to defend that, and the way to do that is through politics. The way to do that is through a combination of hard legislative work and overarching symbolic victories. Bernie Sanders gives us both.

My friends in the establishment of the Democratic Party will accuse me—have accused me—of two things. The first is making the party weaker by dividing it. The second is equating Hillary with the Republicans. I reject both of those statements. If Hillary cannot defeat Bernie Sanders, she would lose the general. And, as I think every Democrat knows—as I have certainly made clear—Hillary is far better than the best Republican. But I’m not voting based on who I think will be a good President.

I am voting for Bernie Sanders because I am a Democrat who believes in the progressive movement. I am voting for Bernie Sanders because I believe that we stand at a crossroads, where we can either register our complaint with the way that the country is going within a progressive and populist and productive movement, or we can sit back and watch the financial elites of this country carry us to victory on a platform of identity politics and liberal guilt that, although it gives us good policies, does not bring with it the fundamental drive for large scale reform. And even if that reform doesn’t happen—I’m a realist, after all—I am voting for Bernie Sanders because I want to make it clear that those reforms are necessary. And, if and when he loses, I will proudly cast my vote for Hillary.